Buddhism’s bad boy: the fall of Sogyal Rinpoche

Buddhism’s bad boy: the fall of Sogyal Rinpoche

The Tibetan lama, whose violent outbursts include punching a nun in public, stands accused of sexual, physical and emotional abuse at his Rigpa organisation and using his teachings to shame and blame his victims

Sogyal Rinpoche (right), the Dalai Lama (left) and France’s then first lady Carla Bruni Sarkozy attend the inauguration of Lerab Ling, in southern France, on August 22, 2008. Picture: AFP

In August last year, Sogyal Rinpoche, the Tibetan lama whose book The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying (1992) has sold more than three million copies around the world, and made him probably the best known Tibetan Buddhist teacher after the Dalai Lama, gave his annual teaching at his French centre, Lerab Ling.

Sogyal’s organisation, Rigpa – a Tibetan word meaning the “essential nature of mind” – has more than 100 centres in 40 countries, but Lerab Ling, situated in rolling countryside in L’Hérault, is the jewel in the crown. Boasting what is said to be the largest Tibetan Buddhist temple in the West, it was formally opened in 2008 by the Dalai Lama, with Carla Bruni Sarkozy, then France’s first lady, and a host of other dignitaries in attendance.

Sogyal is regarded by his students as a living embodiment of the Buddhist teachings of wisdom and compassion, but a man who teaches in a highly unorthodox way, known as “crazy wisdom”.

At Lerab Ling, more than 1,000 students were gathered in the temple as he walked on stage, accompanied by his attendant, a Danish nun named Ani Chökyi. Sogyal, who is 70, is a portly, bespectacled man who requires a footstool to mount the throne from which he customarily teaches. Approaching the throne, he paused, then turned suddenly and punched the nun hard in the stomach.

“I guess the footstool wasn’t in exactly the right position,” says Gary Goldman, an American student of more than 20 years standing, who was seated in one of the front rows. “He had this flash of anger, and he just punched her – a short gut punch. Everybody around me kind of sucked their breath in. She started crying, and he told her to leave, get out, and then he started to talk.”

“To see the master not as a human being but as the Buddha himself,” Sogyal has often told his students, “is the source of the highest blessing.” Those attending his teachings are cautioned not to be surprised or to draw “the wrong conclusions” about the way he might behave. Apparently irrational, even violent conduct, it is said, should be viewed as “mere appearance”.

But punching a nun in the stomach ...

“Afterwards, everybody was trying to make sense of what had happened,” Goldman says. “People were very upset.” It was customary for students at the retreat to email any thoughts or questions they might have on the day’s teachings to Sogyal’s senior instructors.

As a young man, Goldman was a United States Army ranger who served in Vietnam. “We all wrote something up,” he says. “I said, I understood his methods were unconventional but punching Ani Chökyi was knocking the ball out of the park.

Sogyal Rinpoche in Paris, in 2003. Picture: AFP

“I’ve seen this kind of thing in the military and we don’t do that any more – at least not legally. But on the other hand, if this was another part of his ‘crazy wisdom’ teaching, we seriously needed to talk about it ...”

The next day, one of the Rigpa hierarchy addressed the doubters. Sogyal, he said, was upset that people should be questioning his methods. If people didn’t understand what had actually happened, then they probably weren’t ready for the promised higher-level teachings, and Sogyal would not teach again during the retreat.

“This is what he does,” Goldman says, “when something comes up he’ll very skilfully manipulate his students to get them back in line. I just thought, ‘I’m done with this.’”

Largely thanks to the benign, smiling example of the Dalai Lama, Tibetan Buddhism has grown enormously in popularity in the West over the past 30 years, for the most part escaping the scandal that has dogged other religious institutions – at least publicly.

Within the Buddhist community, however, Sogyal Rinpoche has long been a controversial figure. For years, rumours have circulated on the internet about his behaviour and, in the 1990s, a lawsuit alleging sexual and physical abuse was settled out of court. Yet his position as one of the foremost Buddhist teachers in the West has remained remarkably intact – until now.

In July, eight senior and long-standing current and former students sent a 12-page letter to Sogyal. “Long simmering issues with your behaviour,” it began, “can no longer be ignored or denied”, going on to list a catalogue of damning allegations against him.

Sogyal’s habitual physical abuse, the letter alleged, had “left monks, nuns, and lay people students of yours with bloody injuries and permanent scars”. He had used his role as a teacher “to gain access to young women, and to coerce, intimidate and manipulate them into giving you sexual favours”. Students had been ordered to strip, “to show you our genitals”, “to give you oral sex” and “to have sex in your bed with our partners”.

Sogyal, it went on, had led a “lavish, gluttonous and sybaritic lifestyle”, which had been kept secret from the large body of his followers, and financed by donations by students “who believe their offering is being used to further wisdom and compassion in the world”.

You want to progress on the spiritual path, and by sleeping with the teacher you get a closeness to him which everyone is hankering after

“If your striking and punching us and others, and having sex with your students and married women, and funding your sybaritic lifestyle with students’ donations is actually the ethical and compassionate behaviour of a Buddhist teacher, please explain to us how it is.”

Copied to the Dalai Lama, and Sogyal’s most senior students, the letter quickly went viral, shaking the foundation of Rigpa to the core. For Sogyal himself it was the prelude to the most spectacular fall from grace.

More than just a sordid story of an errant spiritual teacher, the case of Sogyal Rinpoche is a symptom of the perils that may arise when Westerners fall in thrall to esoteric spiritual teachings they may not fully understand, and when Eastern teachers are exposed to the glamour and temptations of celebrity worship.

Kalimpong, West Bengal, where Sogyal was educated in a Catholic primary school. Picture: Alamy

Sogyal Lakar was born in Kham, in the east of Tibet, into a family of traders. Among his followers, he is believed to be the reincarnation of Sogyal Terton, a Tibetan lama who was a teacher of the 13th Dalai Lama (the present Dalai Lama is the 14th). But according to Rob Hogendoorn, a Dutch academic and Buddhist who has researched Sogyal’s background, the only authority for that claim appears to be Sogyal’s own mother. Sogyal had little formal Buddhist training, and it is notable that few in the Tibetan community have ever attended his teachings.

When he was six months old, his mother put him in the care of her sister, Khandro Tsering Chodron, who was the young consort – or spiritual wife – of an eminent Tibetan lama, Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro, who became Sogyal’s effective guardian.

In 1954, the family fled from the invading Chinese army to Kalimpong, in West Bengal, where Sogyal was educated at a Catholic primary school, St Augustine’s. Jamyang Khyentse died when Sogyal was 10 or 11, and his education continued at an Anglican school, St Stephen’s College in Delhi. In 1971, he arrived at Trinity College Cambridge, in Britain, to study theological and religious studies, although he never graduated.

It was in Cambridge that he met Mary Finnigan, then a young Buddhist student, now an author and Sogyal’s fiercest critic, who has been assiduous in her chronicling of his alleged misdemeanours.

At that time, there were only four Tibetan lamas living in the country.

“There was nobody teaching in London and there were no centres,” Finnigan says. She arranged Sogyal’s first teachings, in the squat where she was living in London, and would remain his student until 1979.

Sogyal was an exotic presence; a Tibetan who could speak fluent English and seemed to know what he was talking about. His following rapidly grew, and with a £100,000 donation from a well-known British comedy actor he was able to establish his first centre in London.

Assuming the honorific Rinpoche (it means “precious one”) Sogyal set himself up as a teacher in the Vajrayana, or tantric, tradition – a deeply esoteric aspect of Tibetan Buddhism, through which, it is believed, a student can unshackle the chains of ego and attain enlightenment in a single lifetime – “the helicopter to the top of the mountain”, as Sogyal has put it.

Chogyam Trungpa, the Tibetan lama who died in 1987, aged 48, of complications from alcoholism.

It involves the student giving total obedience to the lama in the belief that whatever the lama does, no matter how irrational or incomprehensible it may seem, is for the student’s benefit. Whatever doubts might arise in the mind of the student about these methods is due to “impure perception”.

Tibetan Buddhist lore is filled with stories of great masters – or mahasiddhas – bringing their pupils to enlightenment by methods that appear to verge on madness.

One of the most famous involves the 11th-century mahasiddha Naropa, whose teacher, Tilopa, subjected him to a series of ordeals including leaping from the top of a temple and breaking his bones, jumping into fire and freezing water, and giving his wife to Tilopa as an offering. According to these stories, every time Naropa was broken or near death, Tilopa would heal him with the wave of a hand, giving him an instruction that would bring Naropa’s mind to a more advanced level.

Fundamental to this relationship between master and disciple is the bond of samaya, or trust, in which the pupil not only vows total obedience to the guru, but the guru vows to act only for the benefit of the pupil. Breaking samaya is held to have the most grave consequences, including banishment to “vajra hell” and an infinity of unfortunate rebirths.

“Once you enter into the hermetic world of Tibetan Buddhism, you somehow burn your bridges to Western rationality,” says Stephen Batchelor, a British Buddhist teacher and academic who was himself a Tibetan Buddhist monk for eight years. “You enter a world that appears to be entirely consistent internally; everything makes sense; the structures of power seem to be in the service of these high ideals of enlightenment, and the relationship with the guru is the key element in your capacity to follow this path in the most effective way.”

But the Vajrayana is recognised as a hazardous path, particularly to Western students without a deep grounding in Tibetan culture.

In characteristically lighthearted style, the Dalai Lama has spoken of his own caution in discussing the Vajrayana path. “I have to be careful what I say in teaching, as there are some seekers who might take the Naropa story literally and jump off a cliff, thinking the guru was hinting about it. Not only do I not have the ability to heal the broken body with a wave of my hand, but here in Dharamsala we don’t even have a proper ambulance service!”

A stupa at Gampo Abbey, on Cape Breton Island, in Canada, contains relics of Chogyam Trungpa. Picture: Alamy

In 1976, Sogyal visited America to meet with another Tibetan lama, Chogyam Trungpa, who was regarded as the most extreme exemplar of “crazy wisdom” teachings. Trungpa drank like a fish (he would die in 1987 from complications arising due to alcoholism), openly slept with his students and ran his organisation like a feudal court, surrounding himself with an elite bodyguard, sometimes amusing himself by dressing as a Grenadier guard. “The real function of the guru,” he once said, “is to insult you.”

“Sogyal looked at what Trungpa had,” Finnigan says, “and said, ‘That’s what I want.’”

Like Trungpa, he adopted an unorthodox, often jokey, teaching style, but he was a compelling orator, with an ability to hold an audience in the palm of his hand and convey the Buddhist teachings in a clear and understandable way.

“There are three kinds of people who show up for spiritual practice or information,” Goldman says. “You get the intellectuals who are curious and want to learn something about it; you get the people who are actively seeking truth, and looking to figure out what life and the world is about; and then you get the people who are totally psychologically f****d up – they’ve been abused, terrible things have happened to them. Sogyal was able to satisfy all three groups, very well and very compassionately.”

In 1992, he published The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, which presented traditional Tibetan teachings on a happy life and good death for a Western audience. Clinicians, hospice workers and psychologists applauded it for the comfort it brought to the terminally ill. Comedian John Cleese (Monty Python, Fawlty Towers), an early supporter, described it as “one of the most helpful books I have ever read”.

It was a runaway success, but quite how much Sogyal himself had to do with it is debatable; according to those close to the project, most of the work was done by ghostwriters, including Sogyal’s closest student, and now his right-hand man, Patrick Gaffney.

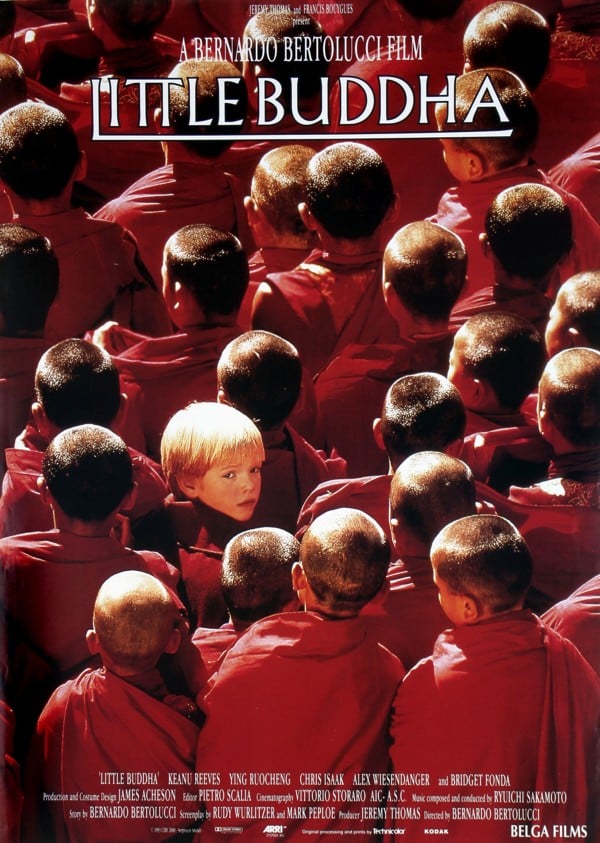

Sogyal appeared in Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1993 film Little Buddha, starring Keanu Reeves.

The book made Sogyal a celebrity. He appeared in Bernardo Bertolucci’s film Little Buddha (1993) and he travelled the world, establishing centres. The combination of Sogyal’s charisma – a purveyor of ancient wisdom in touch with the modern world – and the mystique of Tibetan Buddhism proved a potent lure. Those signing up for his courses had little idea that, as one former follower puts it, Sogyal was “using meditation as a gateway drug into a cult of personality”.

But the first storm clouds were gathering. Sogyal is not a monk, and there is theoretically no prohibition on him marrying or having sexual relations. But his sexual conduct was becoming a cause of increasing controversy in Buddhist circles – not least his surrounding himself with an effective harem of young women, whom Sogyal described as his “dakinis” – a Tibetan term meaning spiritual muse.

In 1994, an American student using the legal pseudonym Janice Doe brought a suit against Sogyal, alleging that using the justification of his spiritual status he had sexually and physically abused her, turning her against her husband and family. This, the charge alleged, was merely one example of a pattern of abuse against a number of women.

Britain’s Telegraph Magazine published a cover story on the case in which two British women spoke about their own sexual encounters with Sogyal.

“You’re chosen, which makes you feel special,” said one. “Because he was my spiritual teacher I trusted that whatever he asked was in my best interests […] You want to progress on the spiritual path, and by sleeping with the teacher you get a closeness to him which everyone is hankering after. I saw it as part of the teachings on the illusory nature of experience and emotions. But, in fact, it caused me a lot of pain that I wasn’t able to dissolve.”

Bernardo Bertolucci’s film Little Buddha. Picture: Alamy

The Janice Doe case was settled quietly out of court. And in a pre-internet age, most readers of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying remained happily oblivious to any hint of scandal. Rather, the book was to prove a powerful medium in bringing him new followers. Among them was a young Australian woman, who would later become a Buddhist nun, taking the name Drolma.

Drolma first read Sogyal’s book as a 21-year-old. “I thought, ‘That’s all very nice, but I don’t need this,’ and put it back on my bookshelf.” Two years later, with her life “falling apart” following an abortion and the break-up of a difficult relationship, she attended a retreat where Sogyal was teaching in New South Wales.

“My life was at a point where I had no understanding of the suffering I was going through, and this provided some answers, and some practical steps, like meditation,” Drolma says.

She became more involved in Rigpa, travelling to Lerab Ling for retreats and facilitating study groups. In 2002, she turned her back on a flourishing career as an artist to become a nun.

“There was this aspect of devotion for the teacher that I felt very strongly. I felt it as the fire of the love of God. And I chose Buddhism because I felt I’d met an authentic example, someone I could follow.”

Even before taking monastic vows, she had witnessed an example of Sogyal’s “crazy wisdom” when he publicly humiliated a male attendant during a teaching session.

“He’d forgotten to put a full stop on the travel plans or something; Sogyal got him to kneel at the foot of the podium and then run backwards and forwards across the tent. I felt terribly uncomfortable but I also thought he was very fortunate to have such close attention from the teacher.”

Sogyal made Drolma his personal assistant, handling his schedule. She would later become responsible for caring for his mother and aunt, Khandro, when they came to live at Lerab Ling. Her duties entailed maintaining a careful rapprochement with the inner-circle of Sogyal’s dakinis.

“Their lives were incredibly pressurised,” she says. “There was lots of jealousy, lots of secrets. If one of them was unhappy or in a mood, then all of us would feel the repercussions, so we also had to do our best to keep them supported.”

The first time Sogyal hit her hard on the head with the backscratcher that he carries everywhere, Drolma says, she accepted it as part of his “wrathful” training. “I thought, ‘Wow, he really trusts me.’” It was the beginning of years of physical abuse and verbal humiliation.

“If he became anxious about his mother, or over a relationship with a girlfriend or some financial thing, he would slap me across the face, or hit me over the head with his backscratcher.”

The first time he punched her in the stomach was in the ante-room of the temple at Lerab Ling, where Drolma was preparing his ritual objects prior to an important ceremony for a visiting lama and his retinue of monks.

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying by Sogyal Rinpoche

Such incidents of violence and abuse were common for those closest to Sogyal, explained away by senior instructors within Rigpa as the lama employing “skilful methods”.

“There was definitely a very well thought-out structure within the Rigpa system that would block the perception of abuse, either by using those historical stories, or making you feel really special if this was the attention you were getting,” Drolma says. “People would say, ‘Please train me, Rinpoche.’”

This author has been given numerous accounts of similar abuse meted out to Sogyal’s closest students: a woman being beaten violently around the head with a backscratcher. A man being kicked, punched in the face, pinned against the wall by Sogyal with his hands around his throat, and hit so hard on the head with a hard-bound practice book that he fell to the floor.

“One goes back to one’s room at the end of a day of [violence], thinking, ‘What the hell was that about,’ but still hanging on to the trust that this is part and parcel of the purification of negative karma,” says one man, who was a student for 20 years.

The thought of reporting Sogyal to the police, he says, never crossed his mind. “These are criminal acts. But the problem is we’ve been complicit, we’ve allowed it, and he keeps doing it.”

In this environment, everything would be rationalised and accepted as “a teaching”. Several ex-followers have described how Sogyal would sometimes address his closest students while defecating, ordering his dakinis to perform the appropriate ablutions as a demonstration of “service”. It is further alleged that among his inner circle, Sogyal frequently took the wives or girlfriends of his most loyal male followers as his sexual partners, either openly or covertly. Men were expected to accept this as part of the teaching. When one complained, Sogyal told his partner the man was “possessed by demons”.

The eight-signatory letter further alleges that on at least one occasion, Sogyal had offered one of his female attendants to another lama for sex.

For a woman to be chosen by Sogyal as a sexual partner was regarded as “an honour”, Drolma says. “It meant they had dakini qualities, and you’re said to be prolonging the life of the master.”

The offerings expected from followers kept Sogyal in a lifestyle of profligate extravagance. At Lerab Ling, he lived in a chalet decorated with cedar-wood panels that overlooked his own heated swimming pool. There was a giant television on which he enjoyed watching his favourite American action movies. In the “lama kitchen”, attendants were available day and night to provide his favourite dishes at a moment’s notice.

In the months that Sogyal was at Lerab Ling, or whenever she travelled with him, Drolma worked 14-hour days, six days a week. “It was always about survival and addressing his most immediate needs for fear of the repercussions if you didn’t.”

On foreign trips, he travelled first class, his retinue with him. Oane Bijlsma, a Dutch woman who joined Rigpa in 2011, going on to become one of Sogyal’s attendants, describes how for an Easter teaching in Britain in 2012, Rigpa took over Haileybury, a public school in Hertfordshire. Sogyal was installed in the music teacher’s house. On his instruction, his students carefully photographed each room, then moved every stick of furniture into storage, replacing it with furnishings more suited to Sogyal’s tastes, including a large flat-screen television with satellite connection. At the end of the six-day teaching, the rooms were restored to their original state. Oane, who was in charge of provisions, was instructed to visit local butchers, taking photographs of the best joints of meat, which she had to submit for Sogyal’s approval, before buying them.

“I was shopping for groceries with hundreds of pounds in my pocket in cash. I was buying ridiculous amounts of the best meats I could get. And the wine and the roses and the chocolates ... And then people in the inner circle would be on stage at the teachings talking about Sogyal living a modest life, and keeping nothing for himself. It was totally obscene.”

“In Tibet a lama would have been under much more control,” one former follower says. “The system would have curbed his excesses. But Sogyal has been surrounded by Western followers who believe that everything he says and does is perfect. It’s a disaster for him, and a disaster for everybody else. He completely lost touch with reality.”

For some within Rigpa, the paradox between being beaten and abused while being told it was for their benefit was causing predictable problems.

“It creates split personalities in people,” one student says. “People feel a loyalty to the teachings which is constantly being contradicted by Sogyal’s behaviour; their hearts are split in two.”

In 2007, Sogyal introduced a programme that he called Rigpa Therapy, in which a number of qualified psychotherapists, who were also Rigpa students, were assigned to treat those entertaining doubts about the teachings. Drolma was among them.

“The crux of every session,” she says, “was exploring how what Sogyal did related to other past relationships in my life. It was all about that, and how my difficulties were nothing to do with Sogyal, and how his blessing was letting me go back to that time and work through it. Basically, the therapists had been brought in to stop people leaving.”

At around the same time, Drolma appeared in a German film about Sogyal, Ancient Wisdom For the Modern World (2008), discussing her relationship with him. “Sometimes he’ll be like my father, like my mother, like my boss, like my friend – like my enemy, because he pushes my buttons,” she said. “But I know always his heart and his motivation is so pure.

“He’s always showing me who I am and who I’m not. The buttons he presses are not who I truly am. The buttons he presses are what needs to be removed. Sometimes there’s a joy when they’re pressed, because it’s showing what needs to be peeled away. Whenever there’s any pain, that’s not the real me hurting; that’s the ego that Rinpoche is trying to eradicate.”

Senior instructors congratulated her on her appearance but her doubts were hardening. “I’d reached saturation point,” Drolma says. She confided her feelings to a visiting Spanish nun. “I’d always been trained to keep everything secret from anyone outside, but I ended up telling her everything. She said, ‘That’s straight out abuse. You’ve got to leave.’”

In 2010, she travelled to Taiwan with three other nuns from Lerab Ling for monastic training. She returned to France, but not to Lerab Ling, hiding out in Paris, ignoring Sogyal’s telephone calls. She fled to India, living in a nunnery, before finally going home to Australia. In 2011, she summoned the nerve to go back to Lerab Ling, for the cremation of Sogyal’s aunt, Khandro.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” she says. “I was in nun’s robes and still keeping my precepts. Wearing robes you have one arm bare, and he touched me there, as if I were a sexual object. It made my skin crawl.” The cremation over, she returned to Australia, and gave up her robes.

“Looking back,” she says, “I think I’d lost all faculty of being able to discern clearly what was going on. He absolutely ground me down. I’m generally someone that’s very trusting of people. And he really took advantage of that.

“And I felt ashamed to leave my friends, ashamed to go back to my family and say I’d made a mistake.” She pauses. “There’s so much shame in all of this.”

A gathering of Buddhist leaders including the Dalai Lama and Sogyal. Picture: Alamy

Within Rigpa, a culture of secrecy and denial prevailed among Sogyal’s inner circle, the worst excesses of his behaviour kept hidden from the thousands of more casual followers who would attend retreats and teachings.

“It’s like an incestuous family, where you keep the secret in the family,” one woman who claims she was sexually abused by Sogyal says. But, inevitably, allegations of impropriety began to leak out on the internet.

In 2011, Finnigan published a document, Behind the Thankas, charting Sogyal’s history of alleged sexual abuse and claiming that there was a sub-sect within Rigpa known as Lama Care, set up specifically to make sure that women were available for sex with him wherever he travelled, and that dakinis had been pressured against their will to take part in orgies. In the same year, a Canadian documentary titled In The Name of Enlightenment was broadcast with more allegations of sexual abuse by former devotees.

In 2015, the president of Rigpa France, Olivier Raurich, resigned, explaining in an interview to the French magazine Marianne that “I had come for teachings on humility, love, truth and trust, and I found myself in a quasi-Stalinist environment and permanent double-talk”. Sogyal, he said, “did not hesitate to brutally silence and ridicule people in meetings. Critical thinking is prohibited around him. Negative feedback never reaches him – only praise is reported because people in the close circle are afraid of him.”

Within Rigpa, Raurich was denounced as an opportunist who was simply seeking publicity for his own career as a meditation teacher.

The following year, French academic Marion Dapsance published a book, Les Dévots du Bouddhisme, containing further allegations of abuse, and the “cult-like” behaviour of Sogyal’s inner circle.

A response posted on the Lerab Ling website described her portrayal as “extremely prejudiced” and “unrecognisable”, invoking the Tibetan teaching of training the mind in compassion, called lojong, with its core principle of “give all profit and gain to others. Take all loss and defeat upon yourself”.

In this context, the letter went on, Sogyal, following the example of “great saints of the past”, would never respond to such allegations.

Ignoring the scandal altogether, in November 2016, Gaffney instead wrote to members of Rigpa, explaining that another lama, and close friend of Sogyal’s, Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche, believing that the next few years represented “a critical period in [Sogyal’s] life” had consulted “a unique clairvoyant master” in Tibet for advice on what should be done to avert “any obstacles to Rinpoche’s life, health and work”.

The “clairvoyant lama” had recommended a number of ritual practices to remove these obstacles. The most important was for Sogyal’s followers to “repair any impairments of the samaya” – their vow of trust between guru and student – by embarking on an intensive practice of reciting mantras. The goal, Gaffney wrote, was to accumulate 100 million 100 syllable mantras every year – a practice that would require 3,000 students chanting for 40 minutes a day.

“If the practices he recommends are done,” Gaffney went on, “then there is every chance that Rinpoche will live until at least the age of 85.”

Some saw it as a subtle way of dampening the growing scandal, and coercing doubting students back in line.

“It was shifting the responsibility for the consequences of Sogyal’s actions onto the students,” one former student says. “To turn your back on the guru is the worst thing you can do. No one wants to go to vajra hell.”

In July, as the eight-signatory letter spread like wildfire, Sogyal wrote an open response to members of Rigpa. He had spent his whole life, he wrote, “trying my best” to serve the Buddha’s teachings, “and not a day goes by when I am not thinking about the welfare of my students.” But in light of the controversy, and following the advice from his own masters about the obstacles arising for his health and life in general, he now intended to enter into retreat “as soon as possible”.

He would also, he went on, “pray and practice for healing and understanding to prevail, and in the spirit of the great [...] masters of the past, take the suffering upon myself and give happiness and love to others.”

Through all the years of rumours and revelations about Sogyal’s behaviour, one group maintained a conspicuous silence. His fellow Tibetan lamas. Sogyal’s large following and considerable wealth made him a powerful figure within the Tibetan Buddhist community. Over the years, he has been generous in his donations to monasteries in Nepal and India, and other lamas have frequently given teachings at Lerab Ling, their visits lending authority to Sogyal’s credentials.

“Tibetan culture is such that it will never criticise another lama, especially one within your own group,” Batchelor says. “But the root of the problem lies in the tantric, aristocratic structure of old Tibetan society that they are seeking to preserve in exile. They’re in the business of holding on to their traditions, not reforming them.

“The problem facing other lamas is that if they accept these criticisms they are basically accepting criticism of the whole system that in a way underpins their own authority; and if they say nothing they know they will be perceived as turning a blind eye to what looks, quite blatantly, like abusive behaviour. It’s a terrible thing if this discredits Tibetan Buddhism, because Vajrayana is a very rich part of Buddhist heritage. But at the same time these abuses have to be addressed.”

The Dalai Lama has frequently condemned unethical behaviour among Buddhist teachers, and urged students to speak out against it in public while never specifically commenting on Sogyal by name. But this summer, speaking in Ladakh, India, he talked of the need to reform the “influence of the feudal system” in Tibetan institutions. Followers, he said, “must not say, ‘this is my guru, whatever my guru says I must follow.’ That’s totally wrong.”

If students found their teachings to be harmful, “you shouldn’t follow the lama’s teachings. Even Dalai Lama’s teachings. If you find some contradiction, you should not follow my teachings.”

“Now recently,” he went on, “Sogyal Rinpoche, my very good friend, but he is disgraced ...”

To the outsider it might have seemed a fleetingly incidental reference; to the Buddhist community it was tantamount to excommunication.

Just a few days after the Dalai Lama’s speech, Sogyal announced he was “retiring” as spiritual director of Rigpa, citing the “turbulence” the allegations around him had caused. There was no acknowledgement of abuse, and no expression of apology or regret.

He would continue as their teacher, though. “Please understand that I am not and never will abandon you! I have a solemn commitment to help bring you to enlightenment and I will never renege on that!”

A Rigpa press release announcing Sogyal’s retirement as spiritual director said that, having sought “professional and spiritual advice”, the organisation would be setting up an investigation by “a neutral third party” into the various allegations; launching a consultation process to establish “a code of conduct” and “grievance process” for Rigpa members; and establishing a new “spiritual advisory group” to guide the organisation.

Rigpa declined to specify what form this independent investigation would take, and also whom the “spiritual advisory group” is likely to be comprised of, saying only that “independent professionals will be engaged to lead the internal investigation and this will probably commence mid-autumn”.

Sogyal’s last public appearance was on July 30, in Thailand, speaking at the Seventh World Youth Buddhist Symposium. His speech, on the subject of meditation and peace of mind, made no mention of the scandal that had engulfed him.

“If your mind is relaxed and at ease,” he told his young audience, “no matter what crises you are facing you will not be disturbed. Even when difficulties come you will be able to turn them to your own advantage.”

Quite how he could now do that is open to question. Following submissions from former Rigpa members, the British Charity Commission has opened a case on the Rigpa Fellowship to assess whether a full investigation into the affairs and governance of Sogyal’s organisation is required. At the same time former students are considering pressing criminal charges.

One leaves a spiritual organisation, Drolma says, with a mixture of feelings – relief, shame, guilt for those left behind.

“I haven’t turned my back on the Buddhist teachings,” she says, “but it was important to let people know what was going on. Sogyal is an abuser, he’s delusional, and he has created real, deep harm for people, and that’s not right in any place at all.”

“It’s like the Buddha said,” Goldman says, “everybody wants to be happy in life. So you join an organisation; you feel good, people are nice, you start to participate more; you invest a lot of time, perhaps a lot of money. At some point it becomes interwoven into your psyche. It’s a part of who you are. And to give that up is incredibly difficult and painful. I saw [Sogyal] as a friend, and on some level I still admire him as an accomplished teacher; but he’s lost his way, and it’s very sad.

“Right now, I’m very unhappy. There’s a hole in my heart. But a lot of people just can’t give it up; they’re tied to him; they’d be giving up an authority figure, probably a father figure; psychologically, it would be a huge loss.”

In July, as the furore over the damning letter from the eight students grew, stories circulated on Buddhist sites of the incident in 2016 when the nun, Ane Chökyi, was punched in the stomach. In response, Chökyi posted a reply on a closed Facebook page, saying that Sogyal’s teachings at the retreat had been “loving beyond any ordinary description” and the punch to the stomach was “taken out of a greater context”.

“I have agreed to the skilful means of my master to purify and transform my delusions into clarity and uproot my attachments,” she wrote. “Sometimes these means can be wrathful and not always a pleasant experience, but that is what I need to be able to see through all the layers of ignorance that keep me blinded and stuck.” Sogyal, she went on, “was definitely not in a fit of rage, there was just a single moment of wrath, which manifested in a soft punch, but it was neither violent or abusive, at least not to my feelings.”

Drolma posted a reply. She could understand Chökyi’s perspective completely, she wrote, because that was how she had once justified Sogyal’s behaviour to herself.

“If the student getting this kind of ‘special training’ has a history of abuse in other relationships in their life (as seems to be the case [for] many of us, including myself), then it is so much more natural, even comforting to receive wrathful attention from someone who is also telling us they love us deeply.”

But then, she wrote, “just like the flick of a switch, I recognised that ‘this is abuse’. And with that, I started to reflect on all the ways in which I had allowed it to happen.

“It was like in The Wizard of Oz, when the curtain is finally pulled back and you realise there is no ‘all-mighty Oz’, there is just a little man shouting into a microphone ...”

Telegraph Magazine