In the 1940s, only 200 families owned 95% of all land in Tibet, and 95% of its people were illiterate. Child labor was rampant, and malnutrition was common. The average life expectancy for serfs in Tibet was 36 years. When the serfs were "taxed," they had to provide various forms of forced labor. Some serfs owed all their daytime labor to the lords, others owed five days a week of unpaid labor, and some were at the disposal of the lord's every whim.

-------------

In 1959, Journalist, Anna Louise Strong, interviewed a former serf name Diedji. Diedji said:

We worked for the lord all the daylight hours and all the days in the year. I first cleaned floors and furniture in the manor and then I worked in the fields in sowing and harvest, and helped to level the ground by dragging wooden plates from my shoulders. I also tended seventeen yaks and cows and milked them when they were fresh. I carried butter and cheese on my back to the lord's house in Lhasa. In slack time I spun wool.

For this work, the lord gave us every month two kes of tsamba for each of us (fifty pounds of barley flour) and every year enough pulu for a suit of clothes, and also a pair of boots. The children got nothing; we fed them from our own tsamba. When our son became a shepherd he also got two kes of tsamba. He was promised clothes, but he never got them. Before he was a shepherd, he worked on the manor and was promised one and a half ke of tsamba but never got it. So since we did not have enough food, we had to go in debt."

-----------

https://historicly.substack.com/p/tibet-china-and-the-violent-reaction

Tibet, China, and the Violent Reaction of a Wealthy Elite

Too many westerners supplant their fantasy instead of dealing with reality in Tibet

Earlier this year, the Dalai Lama, in a BBC interview, said, "Receive them, help them, educate them... but ultimately they should develop their own country. I think Europe belongs to the Europeans.” One can't dismiss his remarks as a mere slip of the tongue. In a 2016 interview with the German newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, he exclaimed, "For example, Germany cannot become an Arab nation."

Oddly enough, too many western journalists seemed surprised that the Dalai Lama holds reactionary views. However, for anyone paying attention, this isn't new. The Dalai Lama once urged the British government to forgive Pinochet and to spare him from being tried for his crimes against humanity because of his age. He has also praised India's far-right Hindu-nationalist leader Modi for his "work."

The Dalai Lama came into the American popular consciousness thanks to Hollywood. During the 1993 Academy Awards, Richard Gere went off-topic in the middle of his speech and appealed to the former chairman of China, Deng Xiaoping, to "free Tibet." It is unclear why Richard Gere appealed to Mr. Deng, who had not held the position of premiere since 1989. Despite this, it became very fashionable for Hollywood celebrities to call for a “free Tibet." How did Mr. Gere come to take up this cause? No doubt he was influenced by Western fantasies about Tibet, such as the 1973 film "Lost Horizon," based on the book “Return to Shangri-la.” Today, we will look at the reality of Tibet.

Tibet was a hard-to-reach area with rough, mountainous terrain, it is sparsely populated. According to population estimates, in 1950, around 1.2 million people were living in Tibet. It was surrounded by mountains on all sides, and before the advent of modern technology and infrastructure, it was hard to access.

Although historians differ on the exact details, it appears that the earliest Buddhist scriptures that were translated into Tibetan appeared around the year 600 AD under King Songstan Gampo. But Buddhism remained a minor religion during this time. We have records of Chinese missionaries who arrived in Tibet to spread Buddhism around the year 800. However, Buddhism was adopted as the official state religion only upon the Mongolian conquest of Tibet.

In the year 1240, Mongolian general Doorda Darkhan invaded Tibet with 3,000 troops. Tibet's army could not match the superior numbers and weaponry of the Mongolian army. There were 500 casualties on each side. Tibet became a de facto protectorate of the Mongol Empire. Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, who ordered General Darkhan to conquer Tibet, created the position of Grand Lama to oversee the development of monasteries and other religious institutions in Tibet. In parallel, the Mongols appointed Mongolian administrators known as "Khans" to supervise the government and administration of Tibet. Tibet would remain a protectorate of the Mongol Empire for another 400 years.

While it is easy to imagine the Lama as some kind of otherworldly spiritual figure who benevolently ruled over Tibet, the reality is at odds with this picture. Near the end of the Mongolian empire, the fifth Dalai Lama faced a rebellion from the Tsang province. He ordered the Mongolian army under his control to exact harsh retribution against the rebels. He said:

For the band of enemies who have despoiled the duties entrusted to them:Make the male lines like trees that have had their roots cut;Make the female lines like brooks that have dried in up winter;Make the children and grandchildren like eggs smashed against rocks; Make the servants and followers like heaps of grass consumed by fire;Make their dominion like a lamp whose oil has been exhausted;In short, annihilate any traces of them, even their names.

Yes, this does sound more like the leader of ISIS than the western orientalist imagination of Buddhism. When faced with any threat to his worldly powers, the fifth Dalai Lama behaved just like the tyrants of all other societies.

With the Mongolian empire waning in the 1700s, the Qing Dynasty took advantage and conquered Tibet, replacing the old Mongolian protectorate. Until then, the rules of succession for the Dalai Lama were murky and confusing. But to maintain control and ensure loyalty, the Qing dynasty got rid of the old grand Lama and installed their own Lama. They renamed the position ‘The Dalai (Ocean) Lama’. To solidify control, in 1792, the Qing Dynasty, adopted a new system of installing a successor to the Dalai Lama that would be done at random. The Qing dynasty protected Tibet from foreign invasions, and the day-to-day administration was left to the Lamas.

In the 1800s, the British unsuccessfully tried to conquer Tibet twice. After the second British invasion under Col. Youngblood, foreigners were banned from Tibet without special permission.

In the early 1900s, Russia, Japan, the USA and Germany all led expeditions to Tibet. Difficult to access, it took 14 days by Yak to reach the capital on a single dirt road from Northern India. Often these explorers wrote about their adventures in a mix of reality and adventurism to sell their books, adding to the mythological version of Tibet.

Tibet Before CCP & The Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama was an absolute ruler. He was guided by a cabinet of nobles and monks called a Kashag. Inequality was written in the law. Society was divided into three classes and nine ranks, with the Dalai Lama at the top. Children of nobles were automatically placed at the fourth-highest ranks at birth. Meanwhile, children of serfs had to be registered and as the property of their parents' feudal estate.

A serf registering her newborn baby with the feudal lord

The Dalai Lama, in his book, My Land and My People, said, "Outside the monasteries, our system was feudal." He was right. Lamaism provided both the religious and governmental aspects of life in Tibet. This system evolved into a hierarchical feudal system that stayed in place until 1959.

In Old Tibet, feudal estates came in two forms: monasteries and large private landed estates. Monasteries were not just a place of worship. Monasteries were all-encompassing enterprises (think Walmart) with large farms, tended by serfs who were listed as property on the land deeds. Many monasteries also maintained their private mercenary forces called the fighting monks. Not unlike drug lords, two dueling monasteries would engage in turf-wars.

An example of a monastery

The bigger monasteries in Tibet were, in fact, entire towns — with large plots of agricultural lands, pastoral lands, thousands of serfs, market centers, banking and lending institutions, military warehouses for the armies raised from among the monastic population. This last was important since the entire monasteries would be turned into military forces if the need arose. They were also centers for publishing, art galleries, and even governmental administrative bureaus in the more remote areas. In nomadic areas, they served important functions, supplying essential skilled crafts and providing a place where the nomads could store their valuables and have a neutral ground in times of conflict.

Serfs carrying goods up and down the Potala Palace

The land that wasn't gobbled up by the monasteries remained at the hands of a few private aristocrats. The aristocrats and the monasteries together built a usurious system to exploit the serfs at every turn.

In the 1940s, only 200 families owned 95% of all land in Tibet, and 95% of its people were illiterate. Child labor was rampant, and malnutrition was common. The average life expectancy for serfs in Tibet was 36 years. When the serfs were "taxed," they had to provide various forms of forced labor. Some serfs owed all their daytime labor to the lords, others owed five days a week of unpaid labor, and some were at the disposal of the lord's every whim.

The accounting books of a typical aristocratic manor from 1951 shows the depths of the forced labor inflicted upon the serfs. The Darongqang manor owned 81 serfs, who were assigned a total of 21,266 days of corvee labor. They worked 11,826 days for the manor and 9,440 days for the feudal government led by the Dalai Lama. The average corvee labor of each serf amounted to 262.5 days per year, or 72% of their annual labor. On top of the forced labor, when the serfs grew any crops on their land, the lords also appropriated a portion of them. Having no worldly possessions, the serfs had to rent both instruments and farm animals at usurious rates in order to work on their share of crops.

In 1959, Journalist, Anna Louise Strong, interviewed a former serf name Diedji. Diedji said:

We worked for the lord all the daylight hours and all the days in the year. I first cleaned floors and furniture in the manor and then I worked in the fields in sowing and harvest, and helped to level the ground by dragging wooden plates from my shoulders. I also tended seventeen yaks and cows and milked them when they were fresh. I carried butter and cheese on my back to the lord's house in Lhasa. In slack time I spun wool.

For this work, the lord gave us every month two kes of tsamba for each of us (fifty pounds of barley flour) and every year enough pulu for a suit of clothes, and also a pair of boots. The children got nothing; we fed them from our own tsamba. When our son became a shepherd he also got two kes of tsamba. He was promised clothes, but he never got them. Before he was a shepherd, he worked on the manor and was promised one and a half ke of tsamba but never got it. So since we did not have enough food, we had to go in debt."

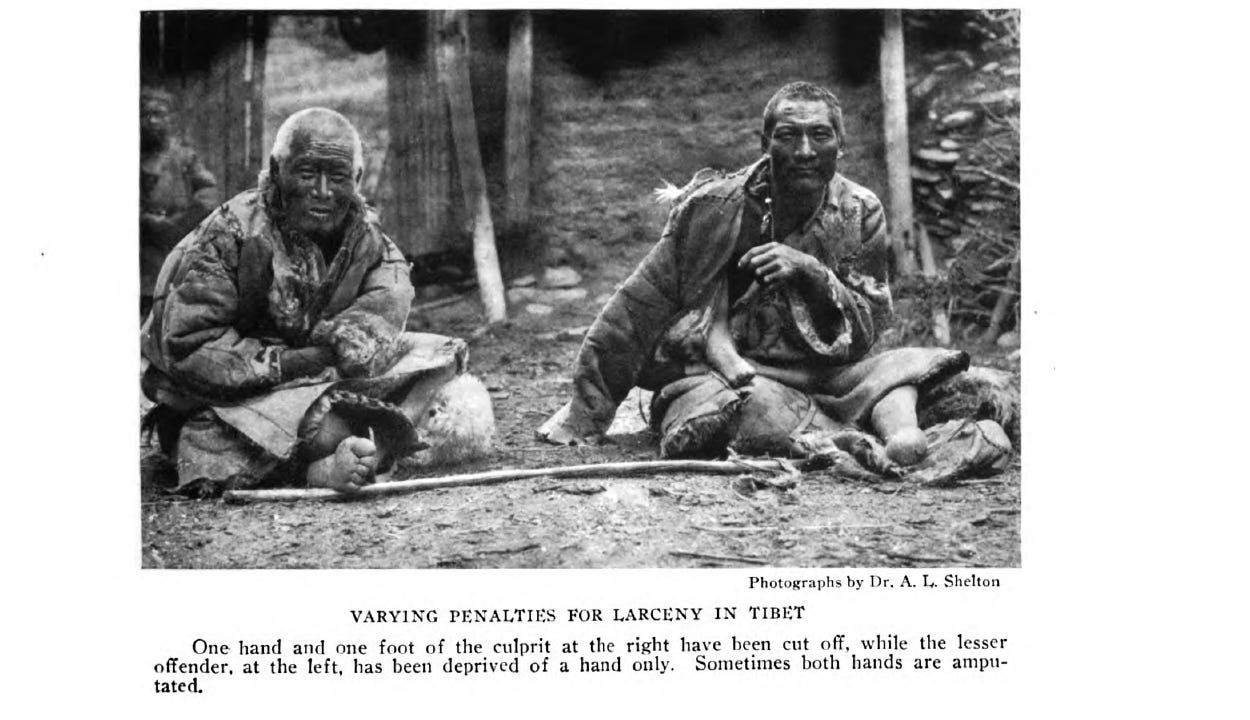

The justice system was unforgiving and cruel. In 1928, National Geographic featured a photo of two men with amputations.

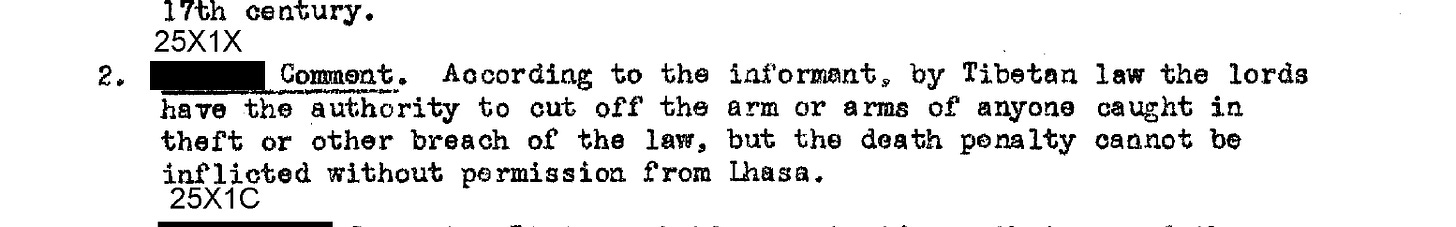

Often serfs were severely whipped for minor transgressions, and some monasteries operated private jails where serfs were tortured. CIA documents from 1950 confirm this [1]!

The serfs were not allowed to move freely about the country and needed the permission of the lord or a government official. In fact, in the book Seven Years in Tibet, Heinrich Heirrer complains about not having the pass to travel to the capital. I also found a document from the OSS, which is a precursor to the CIA that confirms the restrictions on serfs.

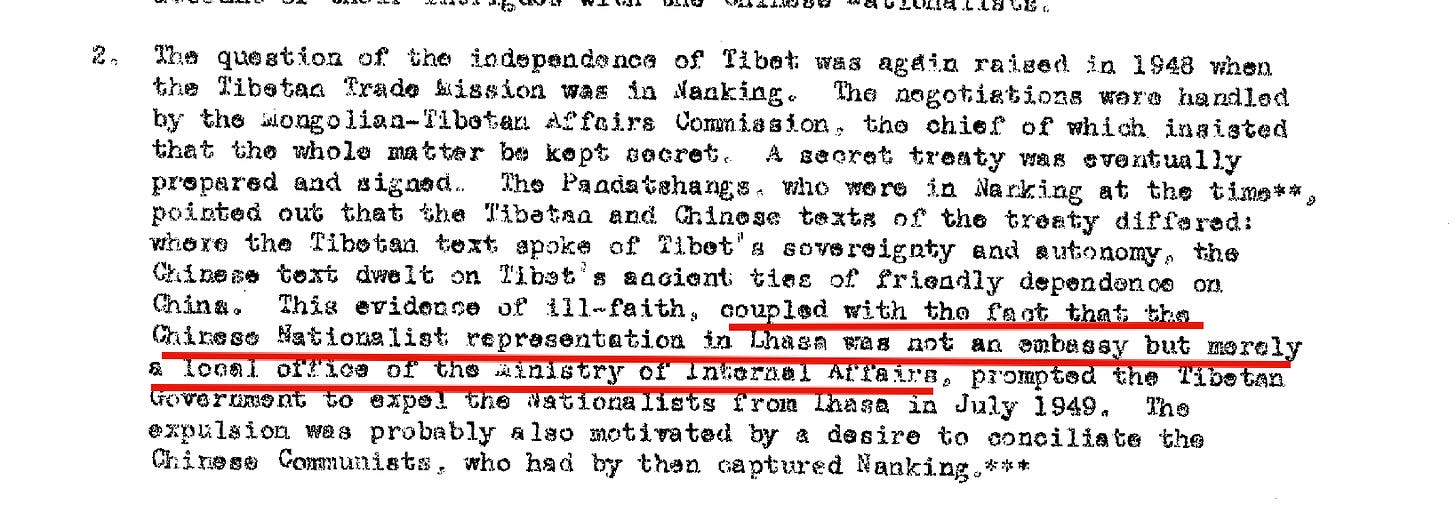

American Position on Sovereignty

The American position on Tibet's sovereignty changed depending on how they felt about the current government of China. During World War II, the US government claimed China held sovereignty over Tibet. In 1948, when Tibetans claimed autonomy, the US state department accused them of having "ill-faith." Tibetan officials even possessed Chinese passports.

However, all of this changed in 1949 after the Communists took control of China. The State Department wrestled with the question of whether or not they should strategically recognize an independent Tibet. They reasoned that it would be advantageous because “Tibet will be one of the few remaining non-Communist bastions in Continental Asia." As the People’s Liberation Army victory became imminent, the US government decided that they supported an “independent Tibet.”

Tibet and CCP

In August 1950, the PLA crossed over into Tibet. Within the first few months, nearly 20,000 Tibetans joined the PLA to fight against the local ruling class. As the PLA marched further into Tibet, they started distributing free food to the hungry serfs, which earned them popular support and aid.

The PLA could have invaded Lhasa in October 1950, but they stopped their advancing troops and sent an envoy to the Dalai Lama asking him to negotiate an agreement. The Dalai Lama, with the advice and consent of the British, agreed to send delegates to negotiate. The PLA soldiers were redeployed to build a road from Beijing to the capital city of Lhasa, Tibet.

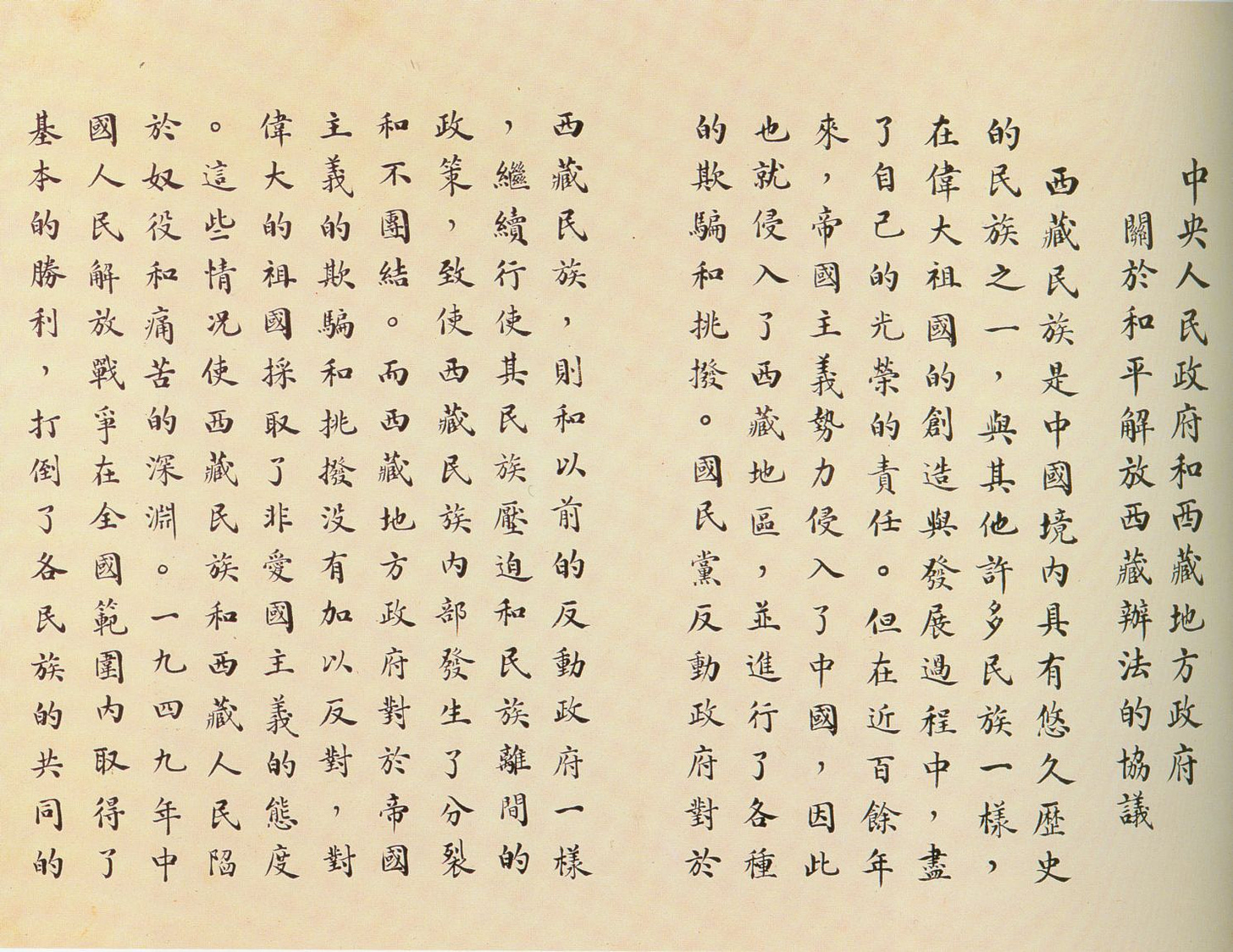

In May 1951, the Tibetan delegates did end up signing an agreement that was quite favorable to the aristocrats. Point 4 of the agreement said, "The central authorities will not alter the existing political system in Tibet. The central authorities also will not alter the established status, functions, and powers of the Dalai Lama. Officials of various ranks shall hold office as usual."

First page of the 1951 agreement between CCP and the Dalai Lama

While the rest of China had immediate land redistributions, Chairman Mao made a concession, and the agreement said, “In matters relating to various reforms in Tibet, there will be no compulsion on the part of the central authorities. The local government of Tibet shall carry out reforms of its own accord, and, when the people raise demands for reform, they shall be settled by means of consultation with the leading personnel of Tibet."

In the next few years, CCP's government did, indeed, build infrastructure projects. The PLA built roads that allowed trucks to travel within the interior. One vehicle, in two days, could carry what sixty yaks took twelve days to transport. Tibetans received more food, and the price of goods dropped by two-thirds in two years. Tibet got electricity. As the New York Times reported, Tibet got its first radio broadcasts. The CCP government also set up a state-bank in Tibet. Peasants received non-usurious loans and very low-interest rates, which made them less dependent on the feudal estates. According to the CIA, PLA also canceled the extremely onerous taxes for the peasants for three years.

They built new schools. According to Dawa Norbu, serfs were given $1 to $1.50 to have their children attend schools, giving serfs more leverage to bargain against the elite class. Even American diplomats like Robert Ford, in their internal documents, wrote in 1955:

There was no sacking of monasteries at this time. On the contrary, the Chinese took great care not to cause offense through ignorance. They soon had the monks thanking the gods for their deliverance. The Chinese had made it clear they had no quarrel with the Tibetan religion.

Even a small loss in power created a violent reaction amongst wealthy elite. Much like other counter-revolutionary forces like the contras in Nicaragua, the Kaibeles in Guatemala, OUN in Ukraine, the Cuban exiles, the wealthy landed class felt entitled to exploit the workers in Tibet. They directed their anger towards the Tibetan peasants who they felt "betrayed" them to the PLA. They engaged in contra-style terrorism against any Tibetan who they felt "collaborated" with the PLA. For example, in 1951, the lamaist rebels killed a Chinese actress and also attacked many PLA troops.

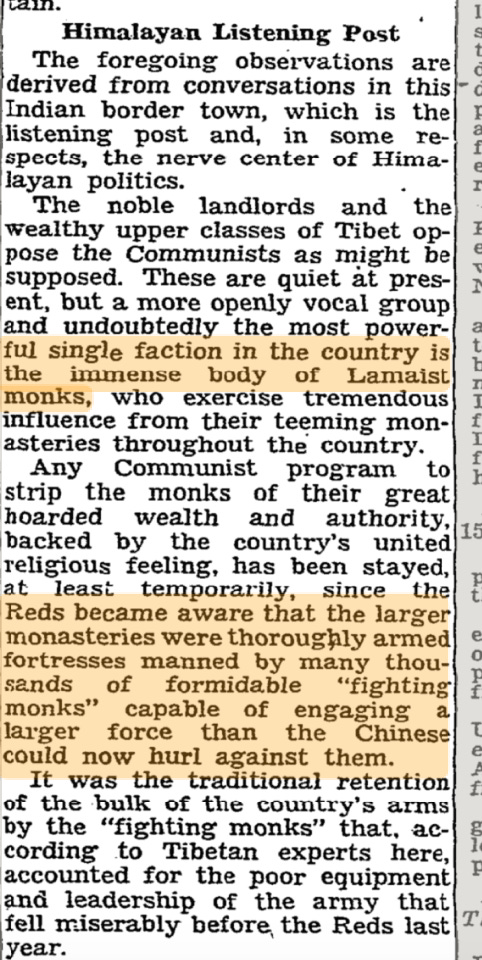

According to declassified CIA documents, from 1952-1958, the CIA trained rebels, mostly from the upper classes, in Colorado to "launch an effective resistance movement." The US also airdropped an overwhelming number of arms, including machine-guns, bombs, grenades, and mortars during this time, most of which was stored in the biggest monasteries.

In 1952, a monk with a mercenary army petitioned the Chinese government against these reforms. A CIA internal document also stated that the monks would take up arms if China redistributed the large land estates in the monasteries.

In 1955, the PLA finally began to ask the elites in Tibet to create a commission for land redistribution. Contrary to their 1951 promise, the elites took up arms after seeing the possibility of losing their lands and serfs. In 1955, Galoin Surkang Wangqen Geleg, of the Tibetan local government, secretly plotted an armed rebellion in Xikang. In 1956, the rebels went to a PLA office building and massacred local staff and peasants, killing over 200 people.

While US Media only paid attention to the elites, the serfs in Tibet felt differently. On July 25, 1956, at least 65 peasants, who couldn't read, put their fingerprints on a letter as a signature and sent a letter to the Dalai Lama asking him to redistribute land. They said, “We are all peasants. We are more anxious for democratic reform than anyone else.”

Serfs carried heavy loads by themselves.

In May 1957, a rebel militia called "Four Rivers and Six Ranges" engaged in violence in the Qamdo, Dengqen, Heihe, and Shannon regions. They burned food warehouses, blew up communication lines, and attacked anyone who they thought collaborated with the PLA. A merchant named Dongda Bazha in Nedong County was captured with his wife because he refused to take part in the rebellion. The wife was gang-raped while Bazha had his throat slit.

However, the "grand finale" was in 1959. All parties agree that the CCP invited the Dalai Lama to an event on March 10, 1959. However, the Dalai Lama alleged that it was a plot to lure him out of Tibet to kidnap him. The CCP denied it. On March 17, no one knows how, but a single shell from a PLA artillery weapon landed in the yards of the Dalai Lama's summer palace, the Potala. His close advisors and his oracle convinced him that he should leave for India and he set out on his journey.

According to the CIA trained fighter, to stop the PLA from "catching" the Dalai Lama, these fighters were ordered to stop the PLA from entering Norbulinka. Ironically, their fear that the PLA would capture the Dalai Lama was unfounded. A few days earlier, Chairman Mao had written to the PLA stationed near Tibet: “If the Dalai Lama and his entourage flee Lhasa, our troops should not try to stop them. Whether they are heading to southern Tibet or India, just let them go."

However, the elites had hired armed insurgents estimated at 20,000. The number of PLA troops in the area was about 5,000. Despite the support of both the landed elites and the US government, they were unable to organize a sufficient army of local Tibetans to fight on their side, so they hired mercenaries from Nepal, India, and even Thailand. For the next few days, heavy artillery was fired from both sides and no one knows how many were killed. During this time, the Potala Palace was destroyed. The west likes to claim that this was "religious persecution," but the rebels were storing their weapons in monasteries, as reported by New York Times on March 27, 1959.

The Dalai Lama, with his CIA-trained crew, fled to India, while the CIA filmed him. He broke the agreement and freed the CCP from their part of the local rule. And serfdom was abolished on March 29, 1959. Here is a video of serfs celebrating their new found freedom.

CCP redistributed lands. Malnutrition then decreased as well as unemployment. Nowadays, people don’t live in shacks and are no longer subject to the draconian whims of the Tibetan lords. Ordinary Tibetans have high-speed rail and also airports.

As with Tibet, the language of colonialism and freedom can be abused by unscrupulous people. Instead of relying on our stereotypes or the media, we must always ask, "Who needs the freedom?" and "from whom?" When we obfuscate class politics, we may end up accidentally supporting the oppressor while demonizing the liberator.

You can download all the documents from the CIA I used to write this piece here

This memo was especially illuminating for me in writing this piece

| 32 | 190 |

No comments:

Post a Comment